Why AI and “helpful” tech are making us helpless

The convenience of technology is eroding key skills

Three months to forget

A recent study in The Lancet sparked a rabbit hole of research about the longer-term effects of leveraging technology in our day-to-day lives. In this study, doctors used AI to spot precancerous growths during colonoscopies, seeing a marked improvement in detections (yay!). Then researchers took the tool away. After only three months of regular AI assistance, the doctors’ unassisted detection rates fell from 28% to 22%. That is a 20% drop in a life-and-death domain.

What bothered me most wasn’t the number. It was the mechanism. The doctors didn’t use AI because they felt less capable. Their skills declined because they were using AI. The tool slowly took over the mental work, and the muscle memory faded. Years of expertise dulled in twelve weeks.

If we zoom out, we know for a fact it’s not just medicine. We are running miniature versions of this experiment every day.

The GPS effect

I’ve driven to certain places in Atlanta dozens of times. (If you’ve had the pleasure of driving in Atlanta, you know how chaotic it can be and how important it is to have alternate routes.). On occasion, my GPS will go awry, and I suddenly can’t remember which street I was supposed to turn on or which exit to take from the roundabout. It isn’t charming. It’s a little scary (and a little embarrassing). I can eventually find my way out, but it can sometimes take a moment for me to regroup.

That isn’t just me being “bad with directions.” Habitual GPS use is linked to decline in hippocampal-dependent spatial memory. Neuroscientists say we become “passive passengers rather than active explorers” when we let the blue line on the screen do the deciding for us. The less our brains need to build mental maps, the less they bother.

Navigation is the obvious example because we all feel it. But this “I can’t do it without the tool” reflex is spreading everywhere.

The great forgetting

Engineering. I hear this from developers all the time: after a few months of leaning on AI coding assistants, debugging instincts get dull. One engineer summed this up well: “I’ve become a human clipboard, shuttling errors to the AI and pasting solutions back into code”. When you stop tracing the problem yourself, you stop seeing the patterns.

Writing. Ask most of us to handwrite more than a grocery list and what comes out looks like cave drawings. Years of typing will do that, but the cognitive cost is real. Handwriting isn’t just about neatness; it supports memory and idea formation.

Math. Calculators used to be for the hard stuff. Now they do the easy stuff too, and students miss obviously wrong outputs because they have lost the gut check.

Researchers even have a name for this pattern: AI-chatbots-induced cognitive atrophy (AICICA), the deterioration that comes from over-reliance on chatbots and similar tools. The label sounds dramatic until your battery dies and you realize you can’t navigate, can’t spell “definitely,” and aren’t totally sure how to approach the bug without autocomplete holding your hand.

Why this fuels burnout

We bring tools in to reduce cognitive load so we can “focus on higher-level work.” Good intention. Wrong model. Abilities do not sit in cold storage while a tool handles them. They weaken with disuse. The less you do a thing, the harder it becomes to do that thing, and the faster your confidence plummets.

That was another finding from the colonoscopy study: once the AI was gone, doctors felt less motivated, less focused, and less responsible for their own decisions. It wasn’t only a performance dip. It was a psychological one.

Now add modern work. Every outage, wrong answer, or broken integration turns into a crisis because we no longer trust our own skills to backstop the tool. What could have been a small inconvenience becomes a spike of panic. This is the problem: we don’t just lose competence. We start to feel incompetent. That feeling is gasoline on the burnout fire.

From helpful to helpless

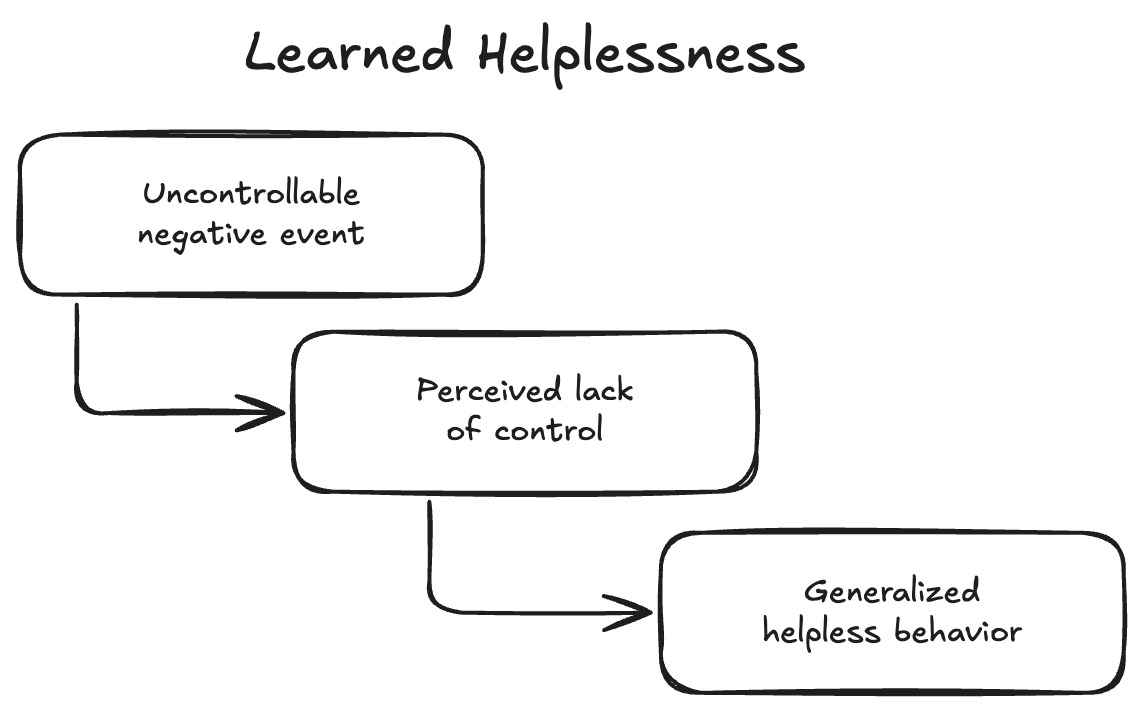

There’s a name for what happens when that panic becomes a pattern: learned helplessness. If you’re repeatedly in situations where you don’t control the outcome, eventually you stop trying, even when you could succeed.

When the default becomes “let the tool do it,” two pillars of mental health crack:

Self-efficacy, the belief that you can figure things out.

Locus of control, the belief that your actions influence outcomes.

Undercut those, and you don’t get peace. You get anxiety. That’s what researchers call technostress—stress driven by the demands and failures of technology at work—and it correlates with higher burnout. Studies of remote workers during the pandemic linked techno-stressors directly to burnout, which then predicted depression and anxiety symptoms.

You can probably name your own triggers:

Your phone dies or you lose cell signal and you cannot navigate.

Spell-check breaks and basic words suddenly look wrong.

The AI insists on a fix you can’t validate, and you realize you don’t remember how to validate it.

Each one is a reminder that the tool holds more of your capability than you do.

What this looks like across jobs

Education research on preservice teachers found that AI dependency had significant negative effects on problem-solving, critical thinking, creative thinking, and self-confidence. These are the people preparing to teach the next generation.

In tech, where AI adoption is furthest along, nearly half of workers report depression or anxiety. It isn’t only the pace or the ambiguity. It is the cognitive dissonance of being told to be innovative while outsourcing the very skills innovation requires.

That is the double bind: use the tools or fall behind, but risk losing the capabilities that made you valuable in the first place.

What to do instead: make AI a collaborator, not a crutch

Throwing the phone in a lake and writing code on a typewriter is not the move. The goal is conscious competence: use tools to extend your reach while keeping your core skills alive.

A few practices that actually help:

Practice deliberate difficulty. Do things the harder way on purpose, regularly. Drive to a familiar place without GPS. Sketch your outline longhand before drafting. Try a debugging session without code suggestions. It is not a test of purity. It is maintenance for the neural circuits you want to keep.

Build tolerance for uncertainty. Resist the reflex to Google or ask the AI the second a question pops up. Sit with the not-knowing for a few minutes. Form a hypothesis. Then check yourself. Uncertainty tolerance is part of the job for any kind of creative or technical work.

Audit your dependencies. For a week, notice the moments you reach for a tool out of habit. Ask, “Could I do this without assistance?” If the answer is yes, try it. If the answer is no, put that skill on your practice list.

Protect the basics. Handwriting, mental math, and spatial navigation pay cognitive dividends well beyond the tasks themselves. These aren’t nostalgic hobbies. They are insurance policies for your brain. (Journaling is a great habit to have for your mental health!)

Create “manual mode” drills. Have a standing block where you operate without the usual scaffolding. For engineers, that might be reading logs and tracing data flow by hand before asking an assistant. For writers, drafting a page without autocomplete and then running edits. For managers, diagnosing a team issue without polling Slack or dropping it in an AI prompt.

Design for outages. If you lead a team, treat tool failure like a fire drill. How do we ship if the assistant is down? How do we make decisions if our analytics dashboard is broken? Write the checklist. Practice it. The point is confidence: “We can still do the work.”

Use the tool, keep the skill. Pair AI with explicit skill-keeping. If you accept an AI suggestion, explain to yourself why it works. If you take a generated outline, rewrite the structure in your own words before you draft. The tool accelerates the start; you keep the thinking.

Where this leaves us

Education researcher Amy Ko puts a fine point on it: unlike calculators, which extended math fluency, many AI tools “supplant thought itself,” short-circuiting the struggle where writing, synthesis, and reasoning live.

The fear is not that AI becomes sentient. The fear is that humans become inert.

The good news is atrophy is not permanent. Doctors can retrain their pattern recognition. We can rebuild navigation instincts, regain math fluency, and remember how to debug without autocomplete. It takes intention and a little discomfort. That’s it.

Real efficiency isn’t outsourcing every ounce of effort. Real efficiency is choosing where effort matters most and keeping our most human skills sharp.

Your GPS might know the fastest route. Do you still know the way home?

thank you for articulating this so well - you so clearly articulated exactly why the tech industry's push towards AI-everything has felt so bad to me